Lines, Paradoxes and Portraits

I handed Zhang Enli paper and a pen and asked him to write a paragraph for "The Kiss" from twenty years ago. He sits down, takes a cigarette from the box, lights it, takes two sips and clips it between the familiar place of his index and middle fingers. "Intimacy, desire, eating, drinking, smoking, joy and sorrow are all in it." He writes.

Left as a riddle, let's talk about the lines first.

For the line, it has undoubtedly welcomed a passionate, fearless and rebellious false death. Almost exactly twenty years ago, when kissing, hugging and gorging on meat were last arranged, Zhang Enli thought, "Enough", then replaced the passion of humanism with the cruelty of the city. Of course it is a fake death, and in another ten years, the savage snake-like lines will be reborn under his pen. Zhang Enli pursued Nietzsche in his youth, and it is here that he laid the groundwork. Just as Zarathustra's worldly wanderings had to go down, up, then down and up again, so Zhang Enli's lines had to go through a cycle of rebirth before a new demon could be born.

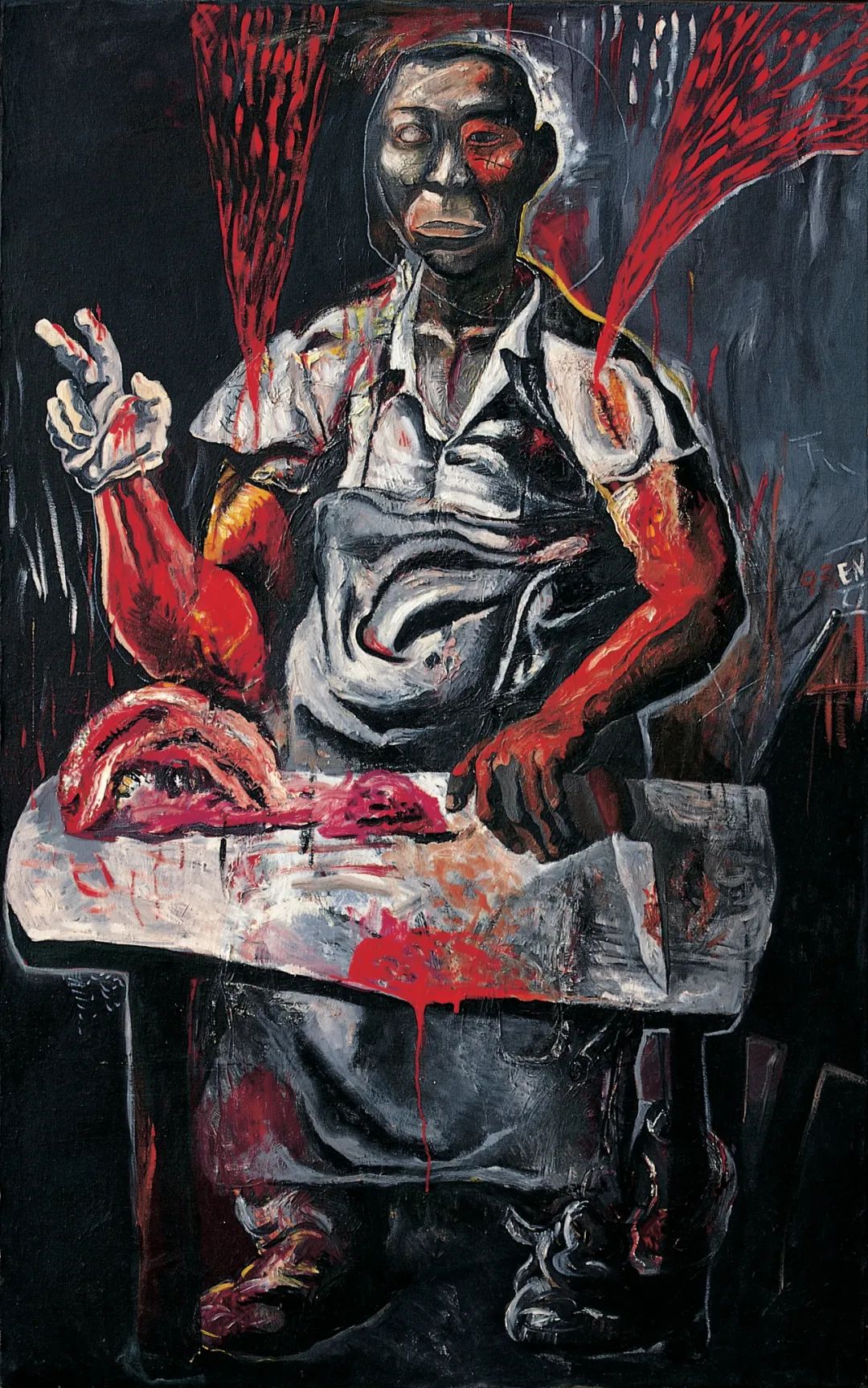

From the beginning, Zhang Enli started painting portraits in the 1990s when he was only thirty years old. Now, this work is exactly the benchmark of contemporaneous art history. But today, let's look at the lines first. The characterization is superficially strong and unsettling, but essentially concealed. It means that the life that the line brings out, including but not limited to restlessness, repression, liberation, joy, surprise, and struggle, and it must be revealed through its own tension. The lines are restrained, or rather cunning, to prevent the voyeur from seeing their original faces, so they put on masks disguised as wrinkles, such as the lines of muscles, the folds of shirts, the sagging contours of hips, and begin an unrestrained revelry. The characters are bloodthirsty, and the slightly numb ones seem to have their eyes opened in anger, which Zhang Enli named the "butcher" stage.

The more precise the appearance of the characters, the more blurred the human state becomes, and the more hidden the lines become. The concealment of the line, or the performance of the mask, means that it has not yet regained its sovereignty. Still, it submits to the symbolic tyranny of the figurative world, finding ways to fawn over a fold, a trace. Even if it is domineering, it can only vaguely reveal its free will in the streamlined body of its form.

It was only when the millennium bell rang that the line reaped the signal and attacked the figurative world.

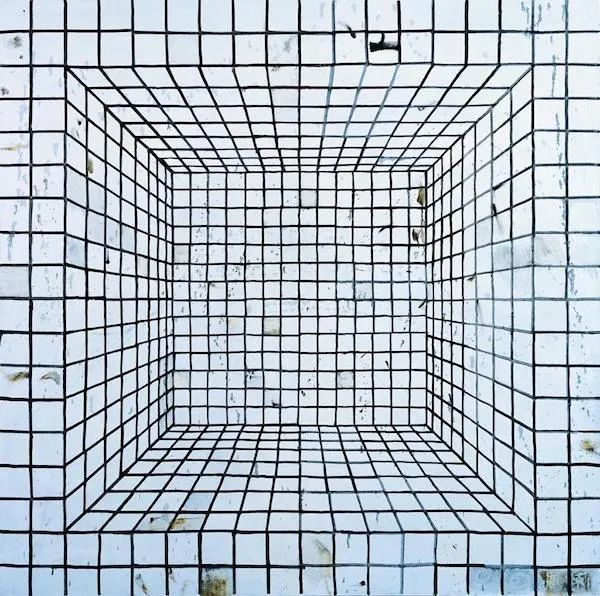

The freedom of line is already visible in the series of everyday objects from 2002, such as in "Sink" and "Bathroom", where the lines of tiles and the lines of perspective merge, indistinguishable from each other and disturbing the center. Once the rope tube series comes, the destructive power of the lines really hardens and becomes threatening. Verbally speaking, the objects presented on the canvas are real lines in the city, such as electric wires and water pipes and ropes that connect you and me inside and outside, in short, they are the products of efficiency. But Zhang Enli's paintings are anything but still life. On closer inspection, the fracture of brush strokes, the thickness of acrylic, the diffusion of light, and the dislocation of gravity all emerge, in his own words, as "slight emotions" and "the state of the city".

Obviously, the lines have revealed their true ambition. For large-size paintings, a closer look must concentrate the view on the local. And when it comes to the local, the title and the mutual suggestion of the elements are no longer effective. At this point, the line is merely a line of paint, with a clear stroke of ink. But in just a moment, millions of images break out from the paint, such as the molting snake skin, the collapsed flesh sac, and the trajectory of the planets. This is the magic power of the lines themselves, related to the subconscious illusion brought by the descent of the physical organs, related to the physical form determined by the heart and blood vessels, in other words, life is the dynamics of the lines, and feeling the lines is almost natural literacy. And through all the illusions, only one essence stands out, and it is the line itself. Thus, the second paradox has to come out here - the more the emotions of everyday objects are slight and steady, seemingly reversing the extreme emotions of the previous decade, the more the lines show freedom and openness of personality. As we can imagine to Kant, the more constraints, the more freedom.

At this point, the figurative world has only one breath left and is on the verge of being pronounced. In the middle of space painting and the abstract portraits that followed, the line broke free from the figurative cage and won a great victory. It is winding, free and wild. Why the middle period, if you ask me? Because earlier spatial paintings, such as the first one made at Objectif Exhibitions in Antwerp in 2007, reproduced his first apartment in Shanghai in the late nineties, only removing the figures and objects and making an alibi, still a figurative phantom. This is also a remarkable point in Zhang Enli's creation, where the end of one series is always connected to the beginning of the next, deliberately revealing traces, such as between the rope tube series and the abstract figures, there are also "far-sighted people" and "connections" covering the old man's retreat. I can't help but think that perhaps the life of a baby really begins with memories.

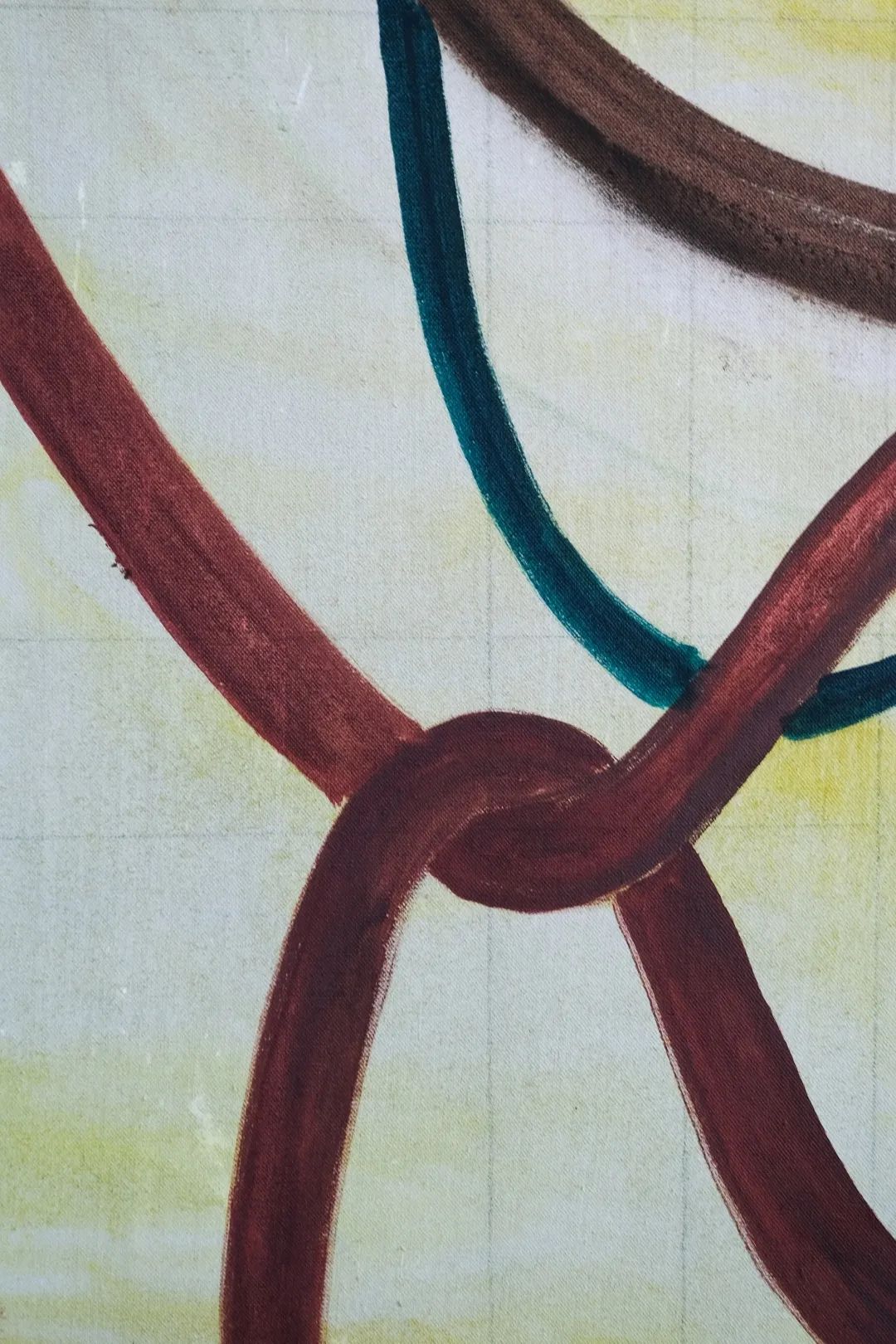

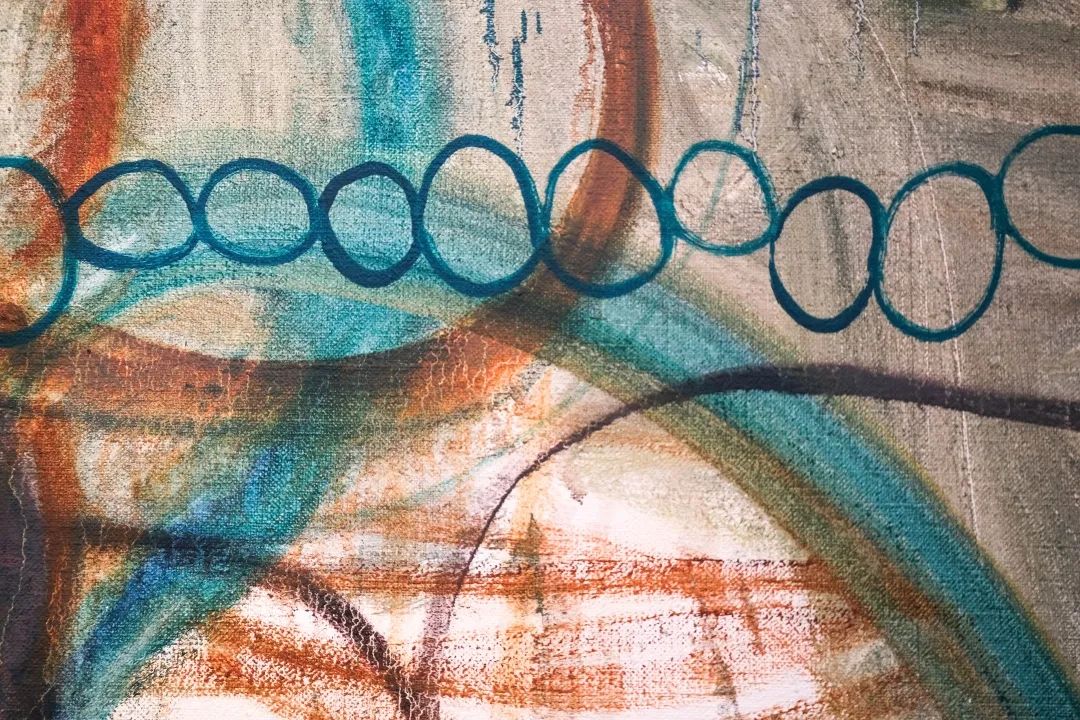

Back to the theme of lines. The line segment at this point presents itself at the forefront with absolute confidence, not retreating, not avoiding, and with an imposing presence. When you look at the painting, a bunch of blue is not finished yet, but the blood red rises, and the ring is intertwined with green, then it suddenly sinks deeper into the color block, and then rises again in the paste above, so that the layers are overlapping and there is no end. It can be compared to music. No matter how the previous lines change and develop, they are always aligned with classical music, up to Schoenberg, lines like notes form the movement, and the movement is like the construction of the mood of the cloth, up and down, before and after, in good order. The lines at this point are far different, having necessarily entered the jazz age, only escaping, not limiting, only undomaining, not constituting, illuminating themselves with themselves and shining themselves, in Deleuze's words, "producing a kind of iteration of the undomained as the ultimate purpose of the music, releasing it into the universe."

And it is more than that. After 2017, the lines directly meet the titles: "Swordsman", "Screenwriter", "Melancholic Man", "Woman in Costume", "Man of Straightforward Character", the more specific the titles and the freer the lines, the deeper the gap between words and images becomes, referring to each other and excluding each other, where does the meaning reside? When he turned his head to ask, Zhang Enli smiled gently (maybe because he has four kittens), "Oh, there were words or images first, I can't tell."

Fortunately, that day, Zhang Enli (as usual) smoked a lot and rarely talked about the other three issues. The line, but a familiar feel, people ask me how to end the old series to open a new chapter, I said is famous then stop, immediately exercise a new feel to go. Paradox, I don't care, I only paint and don't talk about doctrine. Portraits, which are all shadows of myself.

This is the riddle of the opening chapter. The paradox of the eternal life of the image, the narrative is at a loss. What I say is that the joy and sorrow of the era, and what I do is acrylic oil paintings in wooden boxes. Zhang Enli understands, so he is reticent to speak. In the end, only the freedom of line becomes the only joy.