The Flowing Mantle: on the Portraits by Zhang Enli

Shen Qilan Ph.D.

It no longer matters why gravity exists. What matters is that gravity is acting.

It no longer matters whom the portraits depict. What matters is that the realm in which the portraits exist is expanding.

Do they offer visuals or a physical presence?

Zhang Enli makes his decision on the canvas: the portrait he created is a living existence, like the mantle flowing.

I. To Capture the Intangible

Zhang Enli starts his pursuit of the shapeless on the canvas with the use of boxes, leather tubes, twigs, and lines to capture the intangible again and again.

Every painter has experienced the struggle with "form".

From the beginning of his career, Zhang Enli has felt the presence of the intangible. In his paintings, a certain burst of energy always wants to be seen, demanding a form from the canvas.

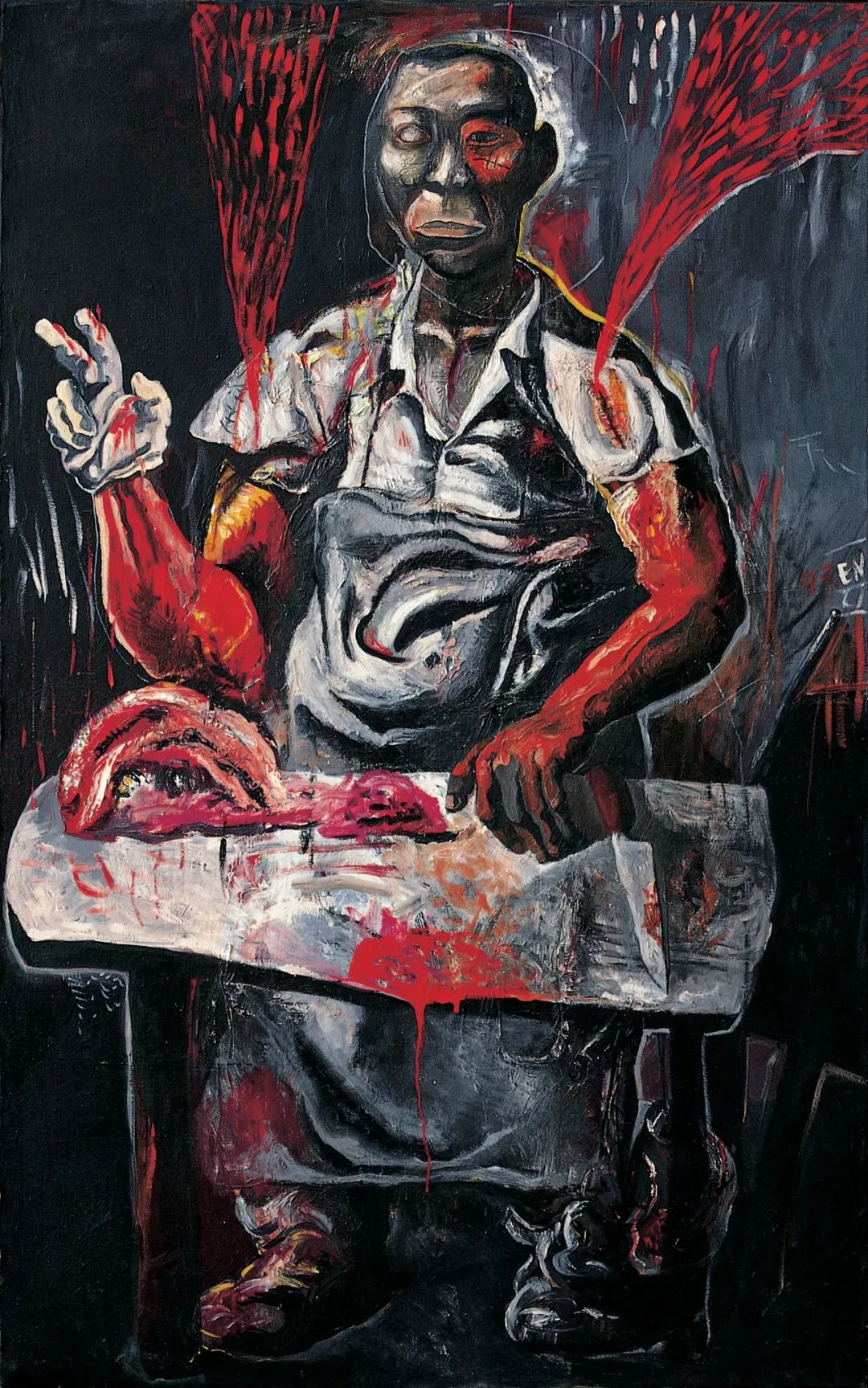

In 1993, he painted Two Jin of Beef, a representative work of the period. It is a portrait of a butcher whose musculature renders him as expressionless as a stone statue. He has an open wound on each of his shoulders that is oozing blood into the air. The spurting blood drops form a shape in the air — on the left, an inverted triangle with flush edges and a flat geometric shape; on the right, a slightly curved geometric shape. These scarlet strokes, which have been refined into points and lines, appear to be gravitationally attracted to the earth. These two streams of blood are perpetually coursing through the painting, whether in 1993 when the painting was completed or being exhibited at the museums (Power Station of Art, Shanghai and Long Museum) in 2020 and 2021. The butcher's wounds still gush with new information and emotions, whether it is helplessness, despair, humiliation, compromise, resistance, anger, pain and shouting. The feelings and vitality conveyed by the painting have not aged or become stale with time. Zhang Enli grasps the power of painting and is deeply aware of the presence of the intangible. These two wounds and the spurting blood are the first clues to comprehending Zhang Enli's portraiture. This is considered Zhang Enli's urban period, during which he painted numerous portraits. The bodies in the images, always bulging and filled with energy, transform into containers in some form.

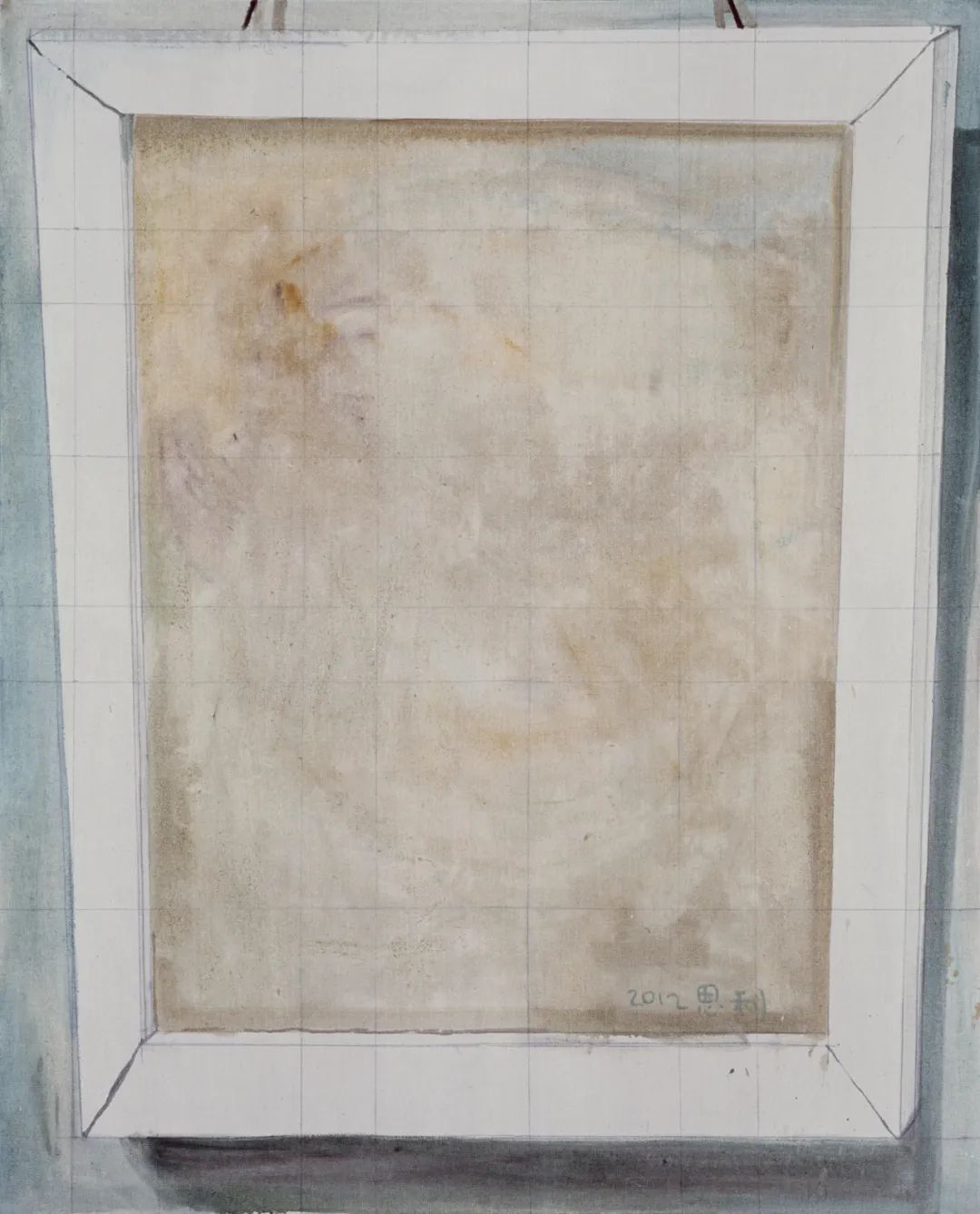

The year 2012 was a significant year for Zhang Enli. He painted Portrait, a white frame with faint traces. With the title Portrait, it seems to be vaguely recognizable as a face: the blurred purplish-grey color could be an ear, but the precise details of the facial features are not clearly identifiable. These blurred colors form a certain feeling, and the title leads these feelings to form an image of the face. In this work, the intangible is encased in a physical frame and spills out of its original boundaries in the viewer's imagination, forming their imagination of the portrait. A thousand people will have a thousand imaginations of the portrait. This work is the second crucial clue to comprehending Zhang Enli's portraiture. By then, he had already investigated the possibilities of the lines without volume and was experimenting with making the line disappear. This Portrait was created at a time when he was painting various other subjects and containers, and he had already begun to consider the nature of the portrait, which he practices in his deduction approach: portraits may be intangible. During that time, a frame was required to hold the portrait. Eventually, he realized that the frame could also be intangible.

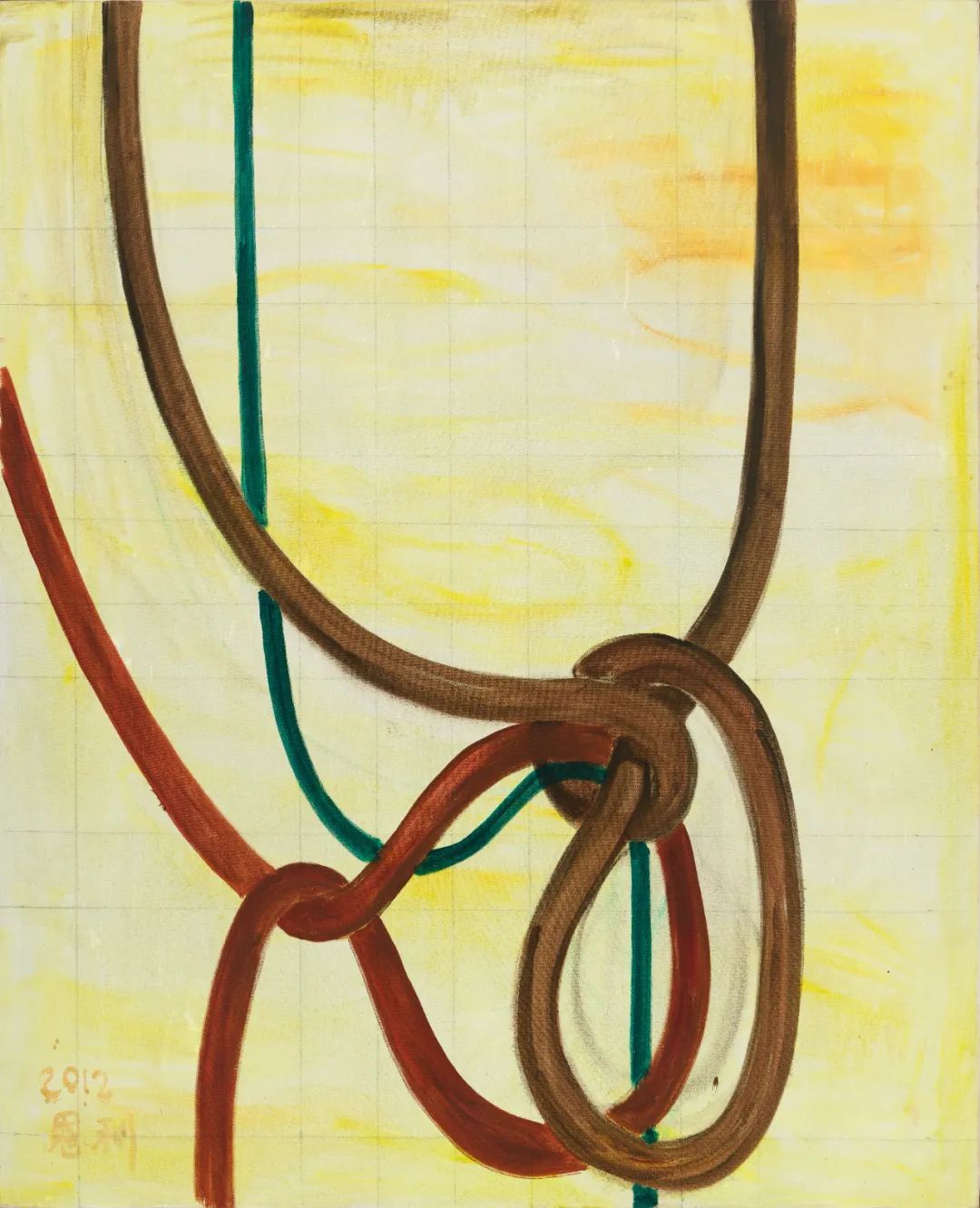

After 2012, Zhang Enli did not immediately take a rushed approach. His practice and exploration of the line are not yet over. He is an extremely patient artist. He is exploring how to use a single line to support the entire image on an eight-meter-long canvas while being incredibly full and intense. He was researching the correspondence between the various curves and the human psyche; he well understood the correlation between curvature and the level of human tension. The water hose became an object that he frequently utilized to convey strength and psychological tension.

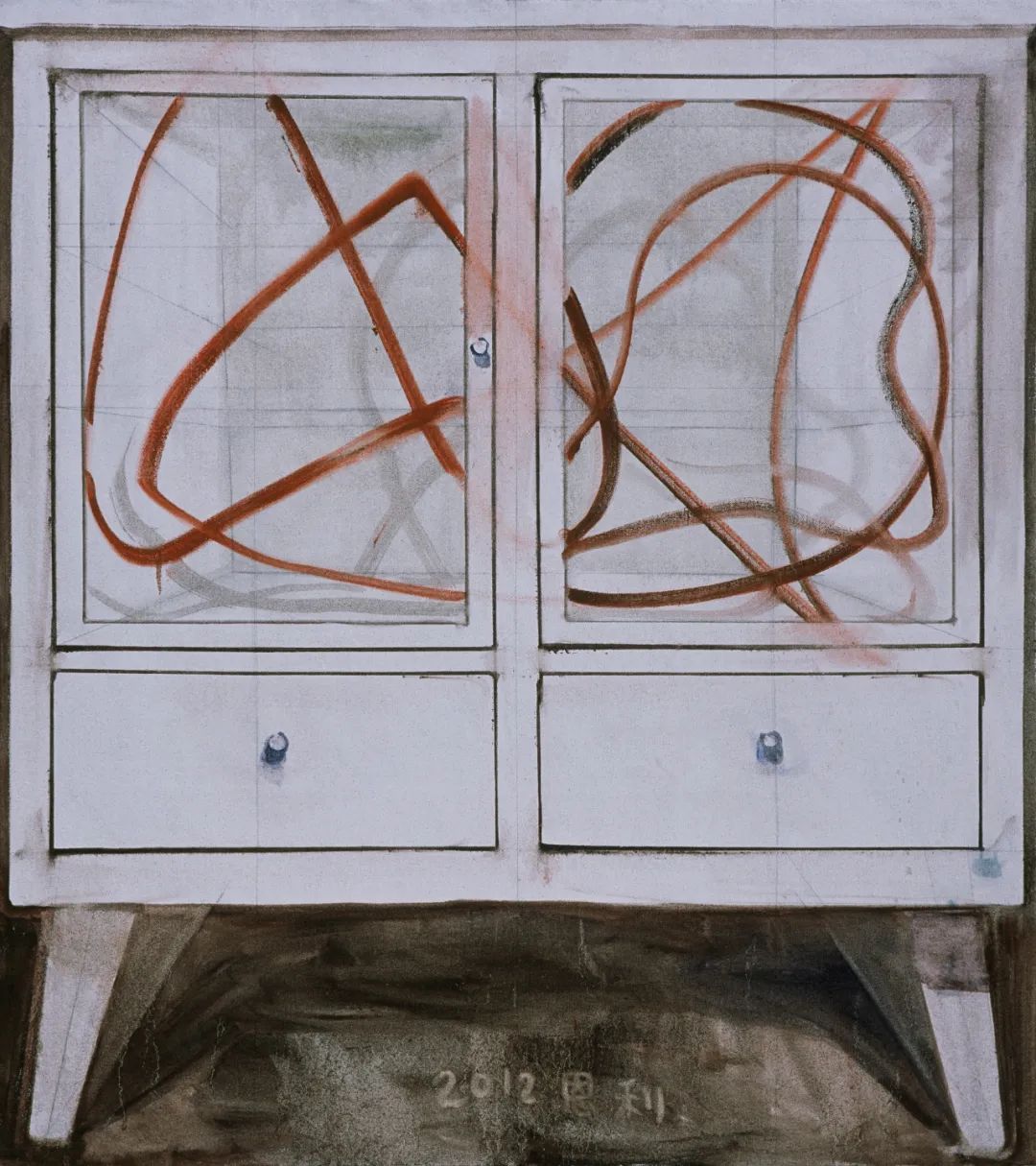

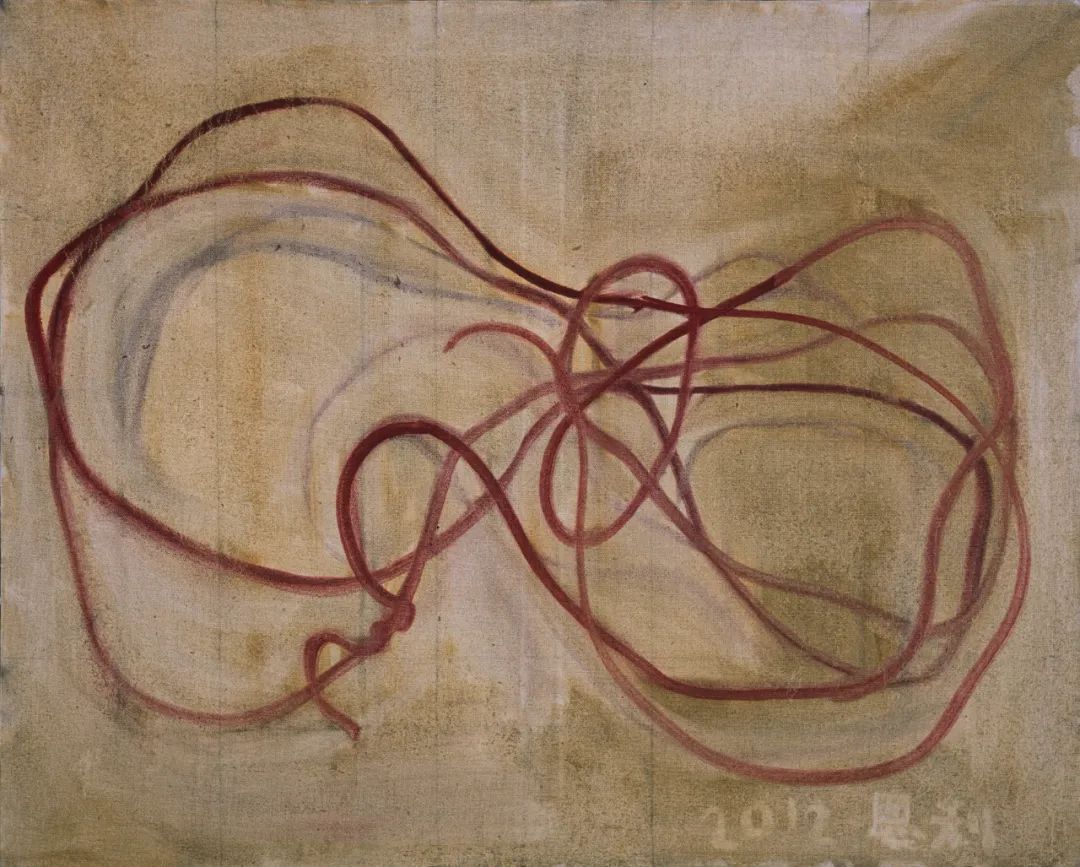

In 2012, Zhang Enli created two line-related works demonstrating his profound contemplation of line and space. He painted History with incredible talent: a white cabinet with an aggressive mass of red lines dancing as if attempting to break through its confining frame. He also painted grey lines, which visually appear to be shadows of the red lines, making the cabinet space more complex and fuller. In this painting, he has used the tangible cabinet to carry the surging lines, and the image is vibrant and full of tension. Form and color are separated, yet they complement one another.

His further exploration is Four Meter Wire - he released the lines from the cabinet. Only the lines exist without the cabinet’s frame and the perspective's aid. Would the painting still stand? Would it still be substantial? This was the adventure of Zhang Enli.

The adventure is successful. With the tension of the intertwining and interlocking lines in Four Meter Wire, a new space is formed on the canvas. The perspective lines promise a visual but simultaneously a psychological space constructed of color and curves. This new space is suspended in the image as if to break away from the canvas and declare independence. It possesses a presence. The intangible is captured and has become visible. At this point, Zhang Enli no longer needs to paint any object to carry the lines; the lines can carry themselves, and the intangible can be perceived through the lines. The lines are free and no longer have to be a counterpart in the real world; they construct their existence and world on the canvas. This is the third crucial clue to comprehending Zhang Enli's portrait works.

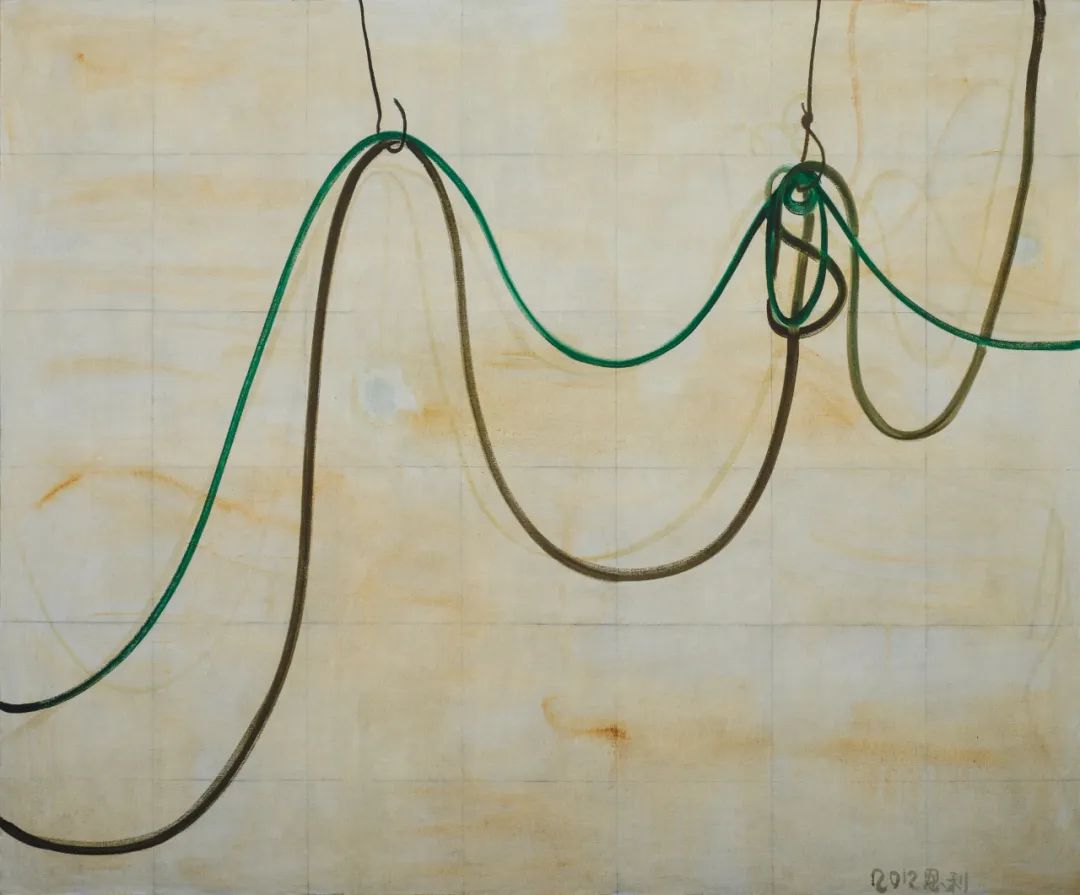

In Elasticity II, voluminous lines pull new space across the canvas, and gravity comes into play. The green hoses gather the viewer's gaze and consciousness, and one feels the space between the hoses, the intimacy between the lines. The psychological fact formed in the image is transmitted beyond the image. It no longer matters why gravity exists. What matters is that gravity is working. Zhang Enli says: "I intended to provoke an immediate reaction in such a way that everyone could feel it."

In The Visible and the Invisible, Merleau-Ponty wrote, "These invisible things form the depths of the visible and support the various visible things." Throughout Zhang Enli's images, it is the invisible that supports the visual and psychological sensations. Zhang Enli brings his feelings to those lines and blocks of colors that carry his sense of the world, contain his understanding of life, and define his inner reality.

A true artist must be proactive in finding problems. After creating works such as Curved Tubes (2015) and Leather Tubes Tied Together (2012), Zhang Enli was not satisfied with the elastic lines that hoses could provide. When he captured the gravity in the intangible, he craved more and desired to fight it again. As he paints, he is pulled by the invisible; in confrontation, he can gain traction on the invisible.

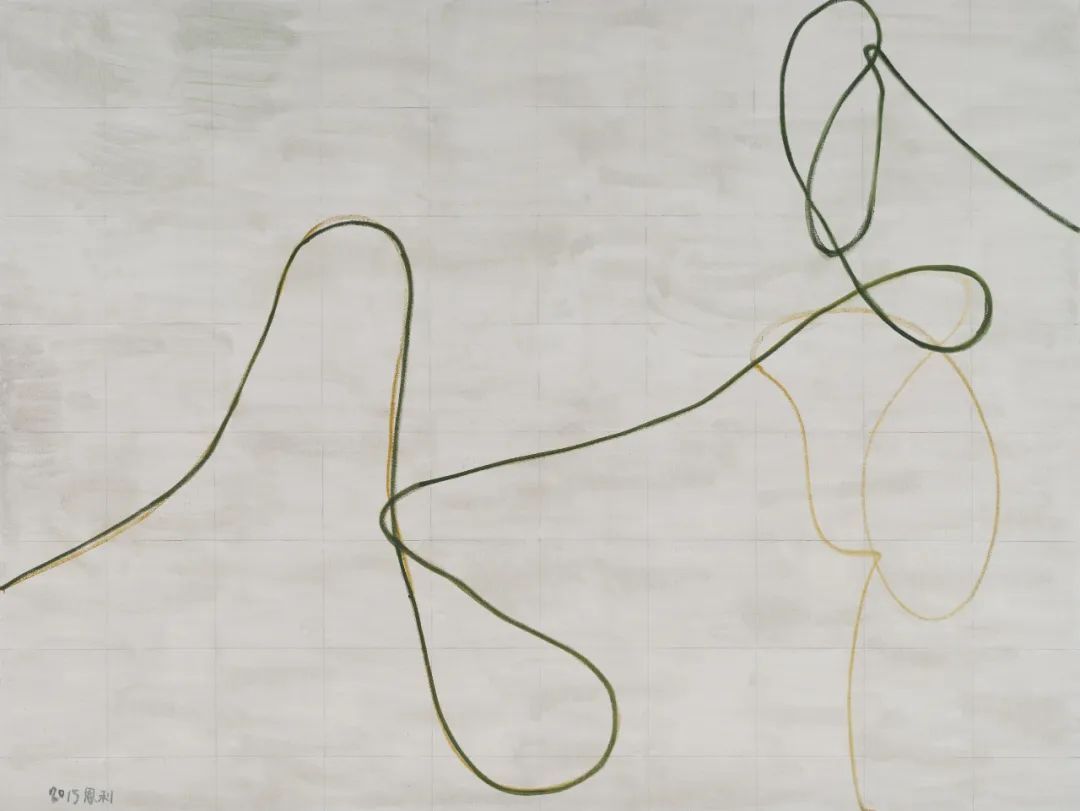

In the Wire series (2015), Zhang Enli expands the possibilities of the lines. The hoses pulled by gravity also pull the viewer's vision. The gaze and consciousness are pulled by gravity on the lines formed by the hoses, possessing an acceleration that brings a sense of pleasure. The lines combined with gravity generate a visually smooth and receptive psychological sensation. By doing so, Zhang Enli wants to create resistance to this sensation by creating lines that are not so smooth, lines that result from human intervention, and lines that leave a mark. The wires unfold in space, and the resulting shapes are the consequence of a combination of forces, including the force of gravity at work and the bend left by human hands. The gaze and consciousness encounter the deceleration and acceleration in the lines, adding to the richness of the psychological sensation. The seeming simplicity and ease of the sequence of lines are formative in its thrill. The intangible, the gravitational force between objects in space, is also a game of force versus force, a dance between the artist and the invisible objects together, forming a certain trajectory that becomes the wires in the paintings.

People felt puzzled and regretful when Zhang Enli stopped painting hoses. But a true artist will not be satisfied with a form that he has already mastered; the relationship between the hoses and space has been almost exhausted by him and failed to satisfy him. More intangibles are awaiting him, and more depth is to be explored.

The Grey Parrot (2017) is an easy-to-feel painting. The lines in the image can be interpreted as the trajectory of the grey parrot left, the path of its flapping wings, or the flow of air. All are possible, the intangible moving through the air like the bursting red lines in the cabinet. Although "there are no traces in the sky, the bird has flown", Zhang Enli captures those traces as a portrait of the grey parrot.

Feel the impulse, the imprint that a person left in time and space, and the world in which that individual resides. As these surges work their way through the mind of Zhang Enli, he decisively picks up the brush and chases these impulses of imagery and feelings on the canvas, pursuing these invisible objects. In Zhang Enli's recent works, he paints directly from the mind, the abstract lines and hues floating freely across the canvas. They become a fluid presence, an intuitive sense of life for the subjects he is painting.

On the surface, Zhang Enli may have undergone several distinct changes - from his initial urban portraits to still life and vessels and in recent years to abstract painting. But the things that attract him remained the same, and the impetus behind his work has kept those invisible presences. His paintings consistently utilize different objects and people to offer viewers a more profound sense of presence through these intangible elements.

II. From the Gaze to the Flow

Portrait painting has a tradition. The history of the faces is the history of the cultures of humanity. Portraiture in European art history has always created the gaze. The face is a stage full of historicity and time.

Erwin Panofsky, an art historian, has emphasized the duality of portraiture: portraits strive to portray what distinguishes the subject from others, what the subject has in common with other human beings, and what remains in him. This iconographic approach applies to portraits that convey substantial concrete information.

In the portraits works of Rembrandt or Van Gogh, as well as those of other masters, the faces of the figures refer to the identities and social roles of the sitters. A portrait is “lifelike” because the painter has rendered a gaze on the two-dimensional plane. (according to Hans Belting) Good portraiture produces a gaze in which the viewers feel that the figure communicates with them. When the viewer gazes at the portrait, the portrait gazes back at the viewer.

Contemporary artists must confront this tradition of the gaze and create their new language of portraiture, breaking with precedent in the process. The artist's task is to restore the face’s historicity, complexity and timelessness.

Bacon's Pope Innocent X reveals the truth of the absurdity of life in a scream. Adrian Ghenie paints not so much a face as an unrecognizable black hole, a black hole of the mind and history that leads to a forgotten history. Ghenie abolishes the gaze but still works the portrait within the framework of “the face.”

Zhang Enli takes another step forward as he cancels the face. He used to say that the back of the head was also a portrait. He painted the hair and back of the heads of numerous individuals. He believed that the face was only a vehicle and that any part of the body could be a portrait of the person. Objects can also be portraits. A cardboard box, a large bed, a bucket, and an old sofa full of signs of usage can all be portraits.

Zhang Enli has painted a series of buckets, painted from different angles. He paints a bucket similarly to how he paints a person – there are a frontal view, a side view, and an overhead view. The buckets on different works are different individuals and do not carry the same message and feeling.

In the portraits of objects, one is still gazing at the objects. Although the objects do not produce a gaze, they coalesce the viewer's gaze and consciousness and are containers for these gazing and consciousness. Old Sofa and Broken Sofa, from 2017, are pivotal works in which Zhang Enli drives the flow of the portrait. The shape of the sofa is no longer recognizable in the picture, but the mottled feeling created by the colors and the soft comfort of the lines are the tactile sensations and memories brought by the old sofa. The picture is like a container that carries the comfort that the softness of the old sofa has brought to the body. The wear and tear suggest the long-term companionship that has developed over time. The process of looking at the Old Sofa is amazing, as the gaze and consciousness seem to sink into the depths of the object (the sofa), and emotions and memories flow, no longer dependent on the shape of certain objects.

Gazing is no longer the first rule of viewing Zhang Enli's works. What he wants to make the viewer feel is the presence directly and be with it in his paintings. Perception and imagination become the key. In Zhang Enli's recent works, abstract lines and colors produce the effect that dismantles the gaze. They provoke a sliding observation and the flow of mental awareness. It can be said that Zhang Enli has created a new language of portraiture.

It is difficult to abolish the gaze and simultaneously create a portrait full of life. Giacometti has repeatedly painted Portrait of Annette to achieve a state of pure perception. What Zhang Enli was pursuing was also a perception of life, a way of painting that breaks away from the depiction. So, he opened the cabinet doors and let out the lines. He drew away the basket filled with balls and let them roll down into free dots and colors, freeing himself from the world of figurative references into the world of the invisible, a world where gravity can be overcome, a painting that is free from the weight of images and logic. He says: "I want to create perfection with an invisible rule."

Zhang Enli says: "The thing I'm thinking about is what is human and how we define human." He means by "the thing" that portraiture points to Being. His portraits, from the gaze to the flow, are a recall of human perception, a rejection of the "mask" symbol, and a challenge to image-centric artistic creativity. His investigation of the portrait pushes the potential of the viewer's perception.

III. The Undercurrent

In life, one is also a flowing vessel full of change.

Zhang Enli believes that viewing is related to the psyche and is a mental activity. He wants to make expressions that are different from previous generations of artists, with richness and complexity. He continues to create shapes and vessels of consciousness, from still lifes to portraits. In Zhang Enli's work, a portrait is an object of "presence," and this presence is fluid.

To give forms to the intangible, Zhang Enli also adopts language, invoking the common human experience. He argues that the two ways in which humans perceive the world are pictorial and nominative. An image provides a visual landscape with a psychological effect. In naming his work, he shares the same struggle that has characterized the centuries-old tradition of portraiture: the search for a balance between particularity and commonality. He values the naming of things and believes that the name of the work is as significant as the image itself.

The names of these portraits have a commonality—each representing a type of person: a wine merchant, a hiker, a screenwriter, a doctor, an English teacher, etc. The names are the non-existent skin of the bag that encases the intangible. Like Zhang Enli's 2011 painting Sack, the invisible object in the sack becomes visible under gravity.

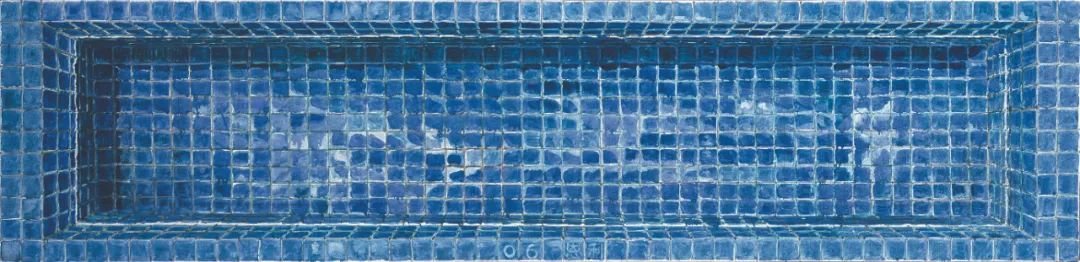

In 2005, Zhang Enli discovered the beauty of mosaics while working on Bath. But he converted the mosaic into his own language in numerous mosaic-related creations between 2011-2013. He created mosaic sinks, mosaic walls, and mosaic interiors.

Perspective Study of a Chalice, by the 15th-century Italian painter Paolo Uccello, showed Zhang Enli the effort expended by the early masters in the pursuit of precision. What he got from the master of perspective was a renewed understanding of perspective. He uses the language of perspective to create his works. In Sink and Mosaic series, he seeks not only to make the means of expression and content as a whole but resistance to perspective. He wants to digest perspective, while the presence he creates resists its absolute command. The mosaic tile possesses a new quality in the image: it is line, form, and structure. It can stand on its own and yet be a reference of sorts. The manifestation and the fading of the sink coincide visually and in moments of psychological feelings. This realizes what interests Zhang Enli most—it is both present and absent".

This quality of "both present and absent" is an important entry point to understanding Zhang Enli's portraits. These abstract portraits of people use line and color to form the shape of consciousness. The title of the work provides a temporary receptacle in which our consciousness can be stored temporarily to form a perception in our minds. The next time we return to the same image, the consciousness in the temporary container will change, and the image will not touch us in the same way.

The poet Eliot's understanding of poetry, echoes this feeling:"For it is neither emotion, nor recollection, nor, without distortion of meaning, tranquility. It is a concentration and a new thing resulting from the concentration of a great number of experiences which to the practical and active person would not seem to be experienced at all; it is a concentration that does not happen consciously or of deliberation. These experiences are not 'recollected,' and they finally unite in an atmosphere ..." (Tradition and the Individual Talent, T. S. Eliot)

Time and again, our consciousness coalesces on Zhang Enli's images, which propel us into the perception and imagination of portraits. Whether it is Young Married Woman, Pâtissier, A Jeweler, Screenwriter or Curator. The portrait manifests and fades in our minds. On the next viewing, they coalesce, take shape and fade away. Each time, the image leads us to a space we did not expect. The shapes and containers of consciousness continue to change, and the undercurrent continues to emerge from the picture.

With interest in "category", Zhang Enli's naming of abstract portraits differs from August Sander's Face of Our Time from the previous century. Sander made portraits that are static, based on existing real-world categories. Zhang Enli works from his feelings in his own spiritual reality, creating a fluid portrait on the canvas.

Great artists are aware of the nature of their work on the canvas, chiseling a deep well about existence. The artist is a special sensor with the talent to detect water, and he points to the depths of existence with his paintings. Water searching is "a talent for staying in touch with the hidden and real presence", bringing to life what is felt and touched. The name Zhang Enli gives to his work is the direction in which the branches of the water seeker show themselves. In doing so, he completes the tug on the viewer's consciousness.

Language is an universal gravitational force of consciousness. The name of the work is the thin eggshell membrane that wraps around the bulging life force of the portrait. Our retinas and sensibilities become the vessels that carry this force.

In naming his works, Zhang Enli looks for the moments when words are formed (the naming moment) and when things take shape in consciousness. He looks for the tension of energy within the words and images. The fluctuation of consciousness brought about by the naming echoes the energy within the image and between the lines. There is no specific counterpart to refer to; viewers must visually ignite the imagination of the mind. In the image, one begins to search inwards for one's own experience, and in between imagination and speculation, the portrait forms a unique manifestation of oneself. This time, Zhang Enli uses the viewer's mind as a vessel. Looking at the canvas, the viewer looks within him or herself and is simultaneously aware of those invisible undercurrents.

It is a wonderful experience. The lines and blocks of colors flow slowly, and it is almost impossible to grasp these intangible objects. But the title of the work gives a container, or a thin film, to gently wrap these soon-to-be-overflowing consciousnesses and imaginations. Like the membrane of the eggshell, light and transparent, it wraps the egg fluid in a film of consciousness, giving it a possible shape, yet it continues to flow!

The appearance is the crustal landscape, and Zhang Enli paints the mantle, the undercurrent. In his picture, above the grid bottom and layers of colors, he kept the earliest outlines that are part of the growth of the portrait at the same time as the movement of the earth's crust. He conceals all the clues beneath the crust. He captures the intangible and escapes psychological gravity once again. His lines break free of gravity, volume, perspective and even the sense of brushstroke. He wants to create a way of painting that has no rules and that is conflicting and harmonious at the same time. He expects everyone to enter the picture through different paths.

Zhang Enli said, "You can only find a way if you don't follow conventional standards."

His portraits try to construct another kind of existential reality, a kind of flowing portrait. The human face is a landscape, like the movement of the earth's crust, always moving and changing quietly in a seemingly stable manner. His portraits are like the movement of the earth's mantle, constantly melting as the viewer's consciousness and gaze continue to capture lines and blocks of colors. The landscape is changing as the mantle is in motion.

Zhang Enli has chosen to transcend the image on canvas to create a new fluid presence. He penetrates the curtain of vision and brings us beneath the crust of the portrait landscape to watch the movement of the mantle.

The mantle always breaks free from gravity and bursts through the earth's crust, turning into lava, flowing on canvas.

Reference

Belting H. (2017). Faces: Eine Geschichte des Gesichts, trans. Shi Jingzhou. Peking University Press.

West S. (2023). Portraiture, trans. Jin Yu. Shanghai People's Press.

Heaney S. (2021). Finders Keepers: Selected Prose 1971-2001, trans. Huang Canran. Zhejiang Literature & Art Publishing House.